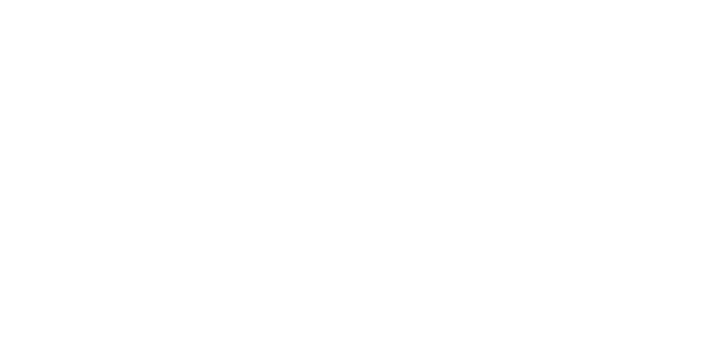

Few people today may remember a time when the Crandell offered more than free popcorn to its members. But Chatham native Mace Sawyer heard all the stories – and still has the sets of dinnerware her grandparents, Edith and George Rochester, received in the 1930s and 40s. “I remember my grandmother saying they got the dishes by going to the movies,” she says. She’s donating them to the Crandell for posterity.

Mace and her late husband, Dwight, who owned Chatham Auto Body Repair for years (now owned by their son) always collected objects “that came from Chatham’s history. I’m giving these dishes back so everyone can see them. Otherwise they will be in a cabinet, where no one can. I want to keep the memories of Chatham alive.”

Chathamite Dale Shannon recalls that Tony Quirino Sr. revived the Dish Giveaway Night tradition in the 1960s. His family received a set of “Pink Dwarf Pine” dishes (above), made by Taylor, Smith and Taylor. (He is also interested in selling them, should you be drawn to their funky midcentury charm.)

“The giveaway promotions of inexpensive dinnerware were one of the most successful solutions that small town and neighborhood movie theater managers found to bring movie patrons back to empty theaters during the Depression,” according to Kathy Fuller-Seeley, a professor of film history at the University of Texas at Austin.

To better understand the origins of Dish Night, you need to start at the advent of sound. The transition to “Talkies” in 1928 into 1929 caused great upheaval in the nascent film industry. Not only was it suddenly more expensive to make films, it was much more expensive to show them. But the Talkies were also hugely successful and put even more people in the seats than silent films ever did. “The American box office rose by almost 50 percent,” says Fuller-Seeley. Anyone who has seen Singing in the Rain, the 1950s musical parody of this time, knows that careers were both sunk and made when actors’ voices were recorded.

The prosperity that came with sound sputtered when the 1929 Stock Market crash catapulted the country into the Great Depression. Stores closed, banks failed, and half of the working population was suddenly without work. “Initially, the one bright spot was going to the movies,” says Fuller-Seeley. “The film industry thought it was Depression proof: people stopped going to baseball games and Broadway, and Vaudeville was dying. But they still kept going to the movies.”

By 1932, however, the Depression caught up with America’s new favorite pastime. The box office lost all of its recent gains and soon dipped lower than it had been during the Silent Era. About one third of small theaters closed their doors for good. So how did the others, like the Crandell, survive? Studios ramped up the nudity, sex and violence for two wild years (think Scarface, Freaks, Tarzan and His Mate, and Baby Face) before censorship, local boycotts and the 1934 Hays Code officially brought an end to all that.

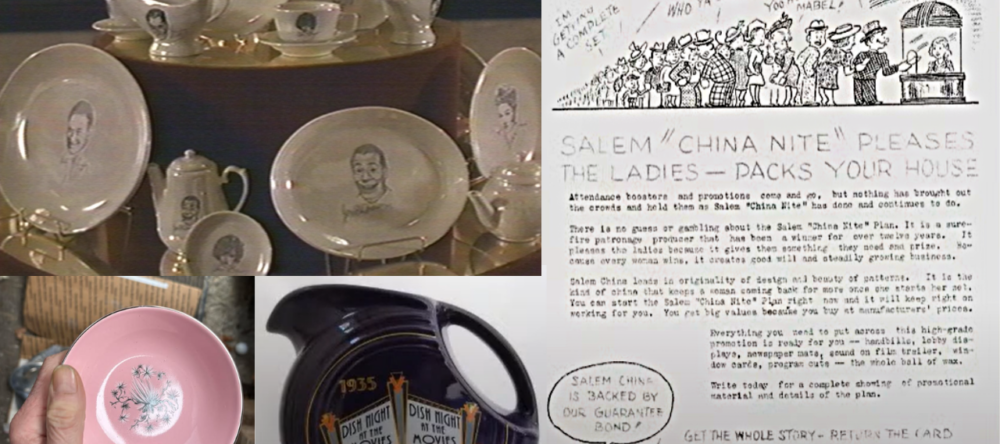

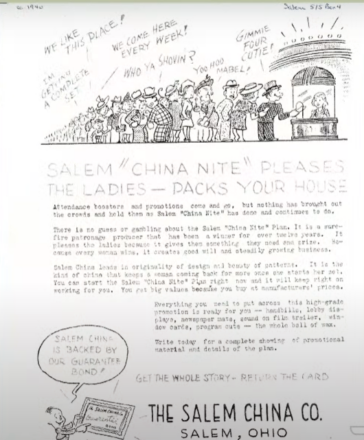

Then came Dish Night, or “China Nite,” as it was called by Salem China Company, one of the earliest of the new mass market dishware companies to advertise the concept to movie theater owners and managers. Starting in the 1920s, these companies had already been giving out promotional dish sets with commercial partners at banks or furniture stores. Salem China Company, in its ads (right), suggested theater owners try something similar, with a potentially bigger payoff: “Salem ‘China Night’ Pleases the Ladies – Packs Your House.”

Usually held on a slower night of the week, the giveaways were a popular draw that sold more tickets than usual. Everyone loved it. “But Hollywood hated dish night,” says Fuller-Seeley, “even though they ended up being saved by it. It really was a brilliant entrepreneurial concept, run by individual movie theaters and managers, that didn’t involve Hollywood at all. It was a real bonus for hard-working mothers who wanted to keep up appearances during extremely difficult financial times.”

Dish night continued through the 1940s, 50s and beyond. In a spoof of the giveaway hysteria, My Summer Story (1994), the sequel to A Christmas Story (1983), features one dish night that turns to chaos. The comedy follows Ralphie Parker and his family in the summer of 1941. Due to a shipping mixup, disappointed housewives end up with a surfeit of Robert Colman gravy boats and no other pieces from the displayed set (bottom left).

Ralphie’s mom instigates a riot when, in frustration, she hurls one of the many gravy boats at theater owner Leopold Doppler. The whole thing lands her in jail (with a smile on her face). Humorist Jean Shepherd, who co-wrote both films with director Bob Clark and narrates both as the adult Ralph Parker, adapted his 1965 short story “Leopold Doppler and the Great Orpheum Gravy Boat Riot.”

Do you stories to share about Dish Nights at the Crandell? We’d love to hear them. Email bmarchant@crandelltheatre.org.